Receba insights e boas práticas sobre inovação de alimentos

Preencha o formulário abaixo e receba conteúdo exclusivo sobre inovação de alimentos

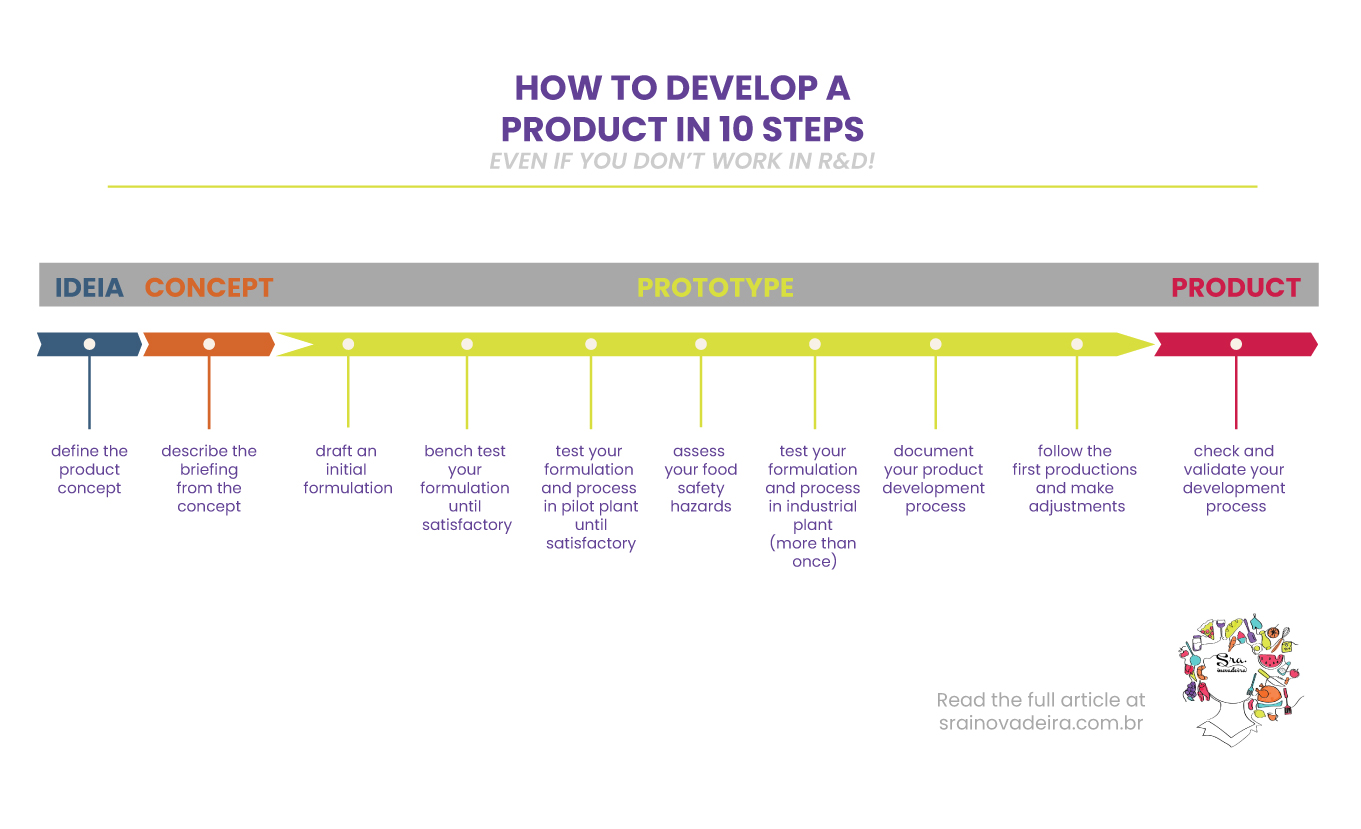

Apart from some – visionary – companies, many Brazilian food companies do not have an R&D department to call their own. Indeed, here is some data: at least 90% of the Brazilian food companies listened to in PINTEC 2008 consider the activities of R&D not very important for innovation. I feel like crying.

In other words: often there isn’t, in the entire organizational structure, a single little box that devotes full-time to transforming ideas into finished products. In these brazuca¹ lands, such activity is most commonly conducted by a correlated area team: Quality Assurance (the most common) or Production (which is often led by a position with the same name as the qualification of the professional who occupies it – Food Engineer, Nutritionist, Food Technician, or related.

Well, I understand you. Sra. Inovadeira sympathizes with you, colleagues who need to keep the production running, ensure food safety, and yet manage to develop every crazy idea that comes out of the boss’s head.

Of course, isn’t it? What else do you have do from midnight to 6am? You sleep? Sleeping is for the weak! ?

Since we don’t want your products to be assisted by the Helping Goddess of the New Products, we’ll give you a step by step guide of what you can do to not go crazy trying to meet your goals.

Probably, in your company there’s someone who swears they have a special communication channel with the consumer (I mean, user). From this person’s privileged mind – or the food that this person sees or consumes – pullulate all the ideas of new products that their company launches. The connection to the public that such a mind has is simply astonishing. People like that are called “psychics”.

Are you your company’s psychic? Don’t be.

Do not assume what your user wishes. Go find out.

Get out of your desk, or the meeting room, and define the concept of the new product in the market, amid people, listening to what they want, what they wish, what aspirations they possess.

Be less psychic and more empathic – you will find a world of opportunities for your company before defining which direction to take on R&D. And you will also be able to align the product concept to your user’s expectations in a much better grounded way, free of clairvoyance and “I think”s.

If you want to learn in practice how to do this step, how about enrolling in our course of Food Design Thinking? Contact us if you want more information about it

You’re going to start from the beginning, aren’t you? So transform those abstract ideas that are wandering in meeting rooms in a document. Make the project requester approve the document (preferably signing it with blood). If you want details on how to set the briefing, here you go.

Briefing in hands, you go to the lab. No, pal: first you search the project database that I know you’ve got there (don’t you?). Oh, my. Take our database of R&D projects as a model and begin to use it).

Have you found a similar product? Use it as a model. You haven’t? No problem – Use the competitor’s product as a model (but don’t go copying it, huh?). No competition? Start with a similar market product and adjust it to fit your goals.

You should observe the list of ingredients, restrictions and requirements of product legislation, desired labeling, balance of additives and cost. A detailed flowchart of how to develop your first formulation here can be found.

Find a scale and the simplest equipment with which you can produce the prototype product. Cookware can replace jacketed tanks, ovens replace dryers, food processors replace cutters. The idea here is not to make the perfect product right away – it’s merely testing the most glaring things of the formulation.

Is the product too salty? Is it too acid? Is the color wrong? Too little flavoring? Strong preservative flavor? Any adjustment you can make in this bench test step save the ingredients needed to make pilot and industrial tests.

Do not underestimate the bench tests, they are important in this first step of the project.

I see a lot of people scribbling formulas in a notebook and going straight to industrial tests – which is not a mistake by itself, but it’s very expensive.

In two aspects:

Therefore, do make a lot of mistakes, small ones. Make a lot of tests, small ones. Take to the industrial test that which already has a good probability of succeeding.

Oh, and don’t forget: Write down all the tests you make and all the results you’ve obtained in each test. Number tests, keep track of each of them – in the future, you will thank me for this when you find, among your notes, the reason for the precipitation of a protein during cooking.

And, please.

2021 – no more need to use formulation notebooks, okay? Old days are gone. There are thousands of ways to protect your precious formulas from hacker attacks (which are probably more concerned about breaking into the CIA and the FBI, anyway).

No. Do not go straight from the bench test to the industrial plant. Find some small equipment – build’em, buy’em, rent’em, borrow them, ask your supplier, work it out! – and test your prototype on a pilot scale.

This is where your product will begin to take shape. Use the pilot-scale test to define your process, evaluate texture, stability, refine the results you obtained on the bench test.

Use the pilot plant tests to gain confidence on the formulation and process to be taken to the industrial test. Here you can still make mistakes, and the cost will be low. Again: Write down all the results you obtained in the tests. Each new attempt is a new test – even if you have employed the same formulation and process.

Record everything, even the things that can’t be measured. Anybody who is developing a product must be a CSI: eyes, ears and nose wide open, sharp palate and tact. The global and attentive perception, using all your senses, must be also recorded (not just what came out in the pH meter or in the texture analyzer).

Do not go into the factory without well evaluating the risks of this formulation and process. If you work in QA, this is not something I need to reinforce, but like they say, better safe than sorry, it’s worth the reminder. ?

It is possible that you are working with ingredients that are already covered in the HACCP plan – it is possible that you aren’t. It is possible that your process is similar to the ones already in place, and that you will use the same control measures — or that you need to by-pass that pasteurizer to achieve the product’s identity. In all cases, assess the risks before putting the product in the plant.

People who develop products must have a systemic perspective when looking at the whole process that involves turning those raw materials into a finished product – and that means also to understand exactly where each risk is mitigated. If there is a risk of heavy metals contamination, is it mitigated within the factory or in the selection of the suppliers? If there is a risk of cross-contamination of allergens, it is mitigated by line separation or by cleanup validation?

Understand what the factory’s current safeguards are and how your product behaves with them. A very simple case that I have already experienced: sieves or perforated plates are excellent barriers for protection against hard and/or sharp fragments above 2mm. Until the moment you need to insert dehydrated vegetable flakes into the formulation – and your beautiful barrier, used in 99% of the products, is gone with the wind.

Preencha o formulário abaixo e receba conteúdo exclusivo sobre inovação de alimentos

Remember: a new product may require new control measures.

And you don’t want to find that out after you’ve contaminated the entire plant with Salmonella.

The time has come for the show to begin: make room in the production schedule with the PPC team, seek help in production team and put this product to run on a large scale! If the rest of the company has no idea what you’ve been developing, it would be nice to set up a meeting – or training – to revise point to point what will go into the factory (before it actually does). This is also the final moment to align with the production and quality teams what should be accomplished during the test.

Remember: An industrial test serves many goals – not just “producing the product”. So prepare yourself to get as many results as possible in one only test, so you will have a more complete panorama to support future decision-making.

Let’s check the most common:

Oh, you tested it once, it worked, can we produce it already? Only if your process is well known and stable (i.e. almost no food process).

It depends, again, on the complexity and variability of your product and process. After all the work you’ve already had, don’t be lazy now: it’s better to keep the product in test phase than to have to handle unexpected problems for the rest of your life.

Have you found the outcome you wanted? Have you come to the formulation and process you needed? Go back to your briefing, analyze it, check if all inputs were met – and document your process (if you did not do this during the previous steps, well, do it now).

Now you just have to include the formula into the management system celebrate, right?

No, no, no, no!

You can only actually say that you development is over, after you have made some deliveries – and here in this post we explained it in more detail.

As you are most likely from the Q.A. or production team, it is already part of your routine: the first “for real” batch enters into production, and you will be there, doing your job. However, remember that the R&D hat remains on your head until the product stabilizes. And that happens in the first production batches.

In fact, industrial follow-up is one of the R&D deliveries after the development process – it is during this monitoring that important decisions about liberation ranges, for example, will be taken.

When you realize that the acceptable fluctuations for the product have already been mapped, it is time to register the conclusions and adjust the product release documents (internal and commercial specifications and what else you use to approve the finished product).

(Just a “small” detail: if step 7 was well executed, it’s not time to make formulation and process adjustments anymore. The product is already developed, so everything should already be running within expected – this is a time to harvest data for more robust statistical analysis, and nothing else.

If you suddenly see yourself in the midst of changes in formulation and process when the product is already being produced for sale, well… you should accept the fact that you are selling tests).

You finished everything, production is stabilized and the product is coming out in conformity? Is it time to celebrate?

Well, here we draw a line between who is actually a food researcher and who’s doing it as a casual job (with all due respect). Even if your position is not “food researcher” or “R&D analyst” (or something like that), you are wearing that hat when you develop a product – so there is still one last step left: validation.

The validation of the R&D process is to confirm that the steps adopted above were adequate and sufficient to meet the briefing. And also to ascertain whether the R&D process designed by the company is suitable for its goals.

Here are some ways to do it:

You want the treasure map? Here it goes:

Now I want to know about you, visionaries: what is the greatest trouble that a person who does not work in R&D has when developing a product?

Maybe I can help you in a next post!

Ps.: Do you see how much work it is to do Research and Development, visionary?

Brazil, in fact, seems to still live a conflict: It is a great market, but it has not yet put itself as a global reference for the Research and Development of new products – even when we talk about multinational companies established here.

However, research conducted on Brazilian soil shows that the existence of this process is a decisive factor for the innovation capacity of a company.

Here is some food for thought: investment in internal research and development activities in the food industry in Brazil is about of 0.15% of its incomes.

In Europe, about 0.27% and in the United States, 0.57%, while Dutch food companies invest more than 0.6%.

One should consider that spending with R&D is not directly related to the relevance of innovation, as this article of Forbes shows– but also there’s no miracle, isn’t it?

If we want a more protagonist food industry – and one that depends less on the fluctuation of the dollar – we have to invest.

How about learning how to manage R&D?

Tacta Food School is presenting the first Training Course in R&D management. It was born from our interaction during the year 2016 – yes, I answered 100% of the emails (more than 1000!), I taught 4 Food Innovation Courses and attended to 3 Meetings of Visionaries.

Always with attentive ears and open heart to understand the demands of these R&D people, who are so special to me. A formation course for those who want to take a step forward in their career, do a lot of networking and put their hands on the most intriguing themes of food R&D.

We’re going to make a revolution in the food market!

Together we can make a great impact through small actions: share this post to spread the message.

¹Brazuca: Brazilian (informal)

Juntos podemos causar um grande impacto através de pequenas ações: compartilhe e espalhe a mensagem.

E mais: participe da comunidade privada de +12000 visionários de alimentos que recebe dicas e insights exclusivos.

Sem spam. Só inovação.

Deixe um comentário